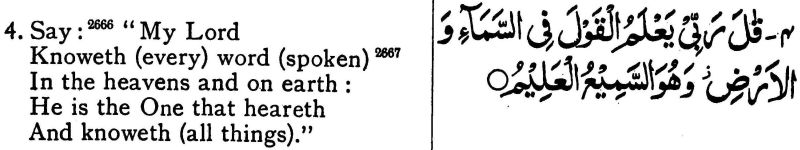

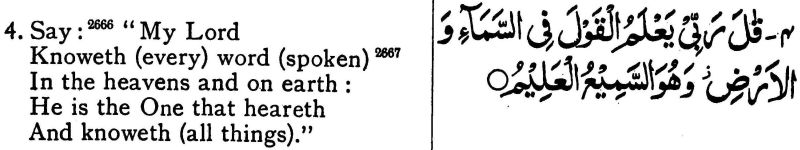

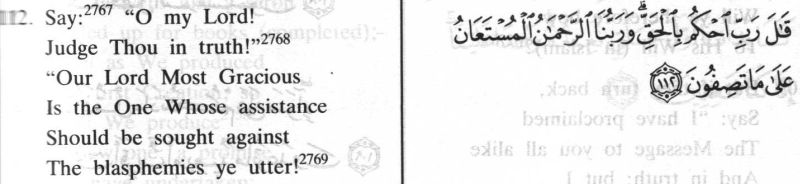

S. 21:4 |

|

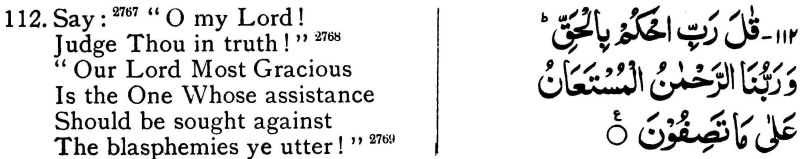

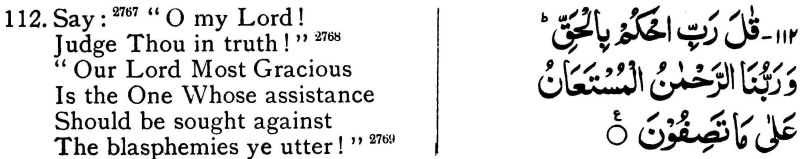

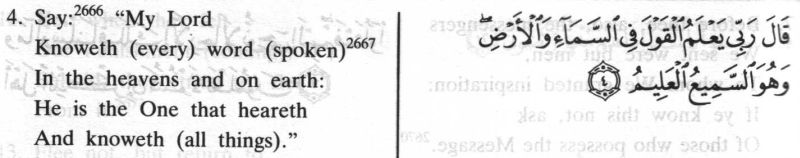

S. 21:112 |

|

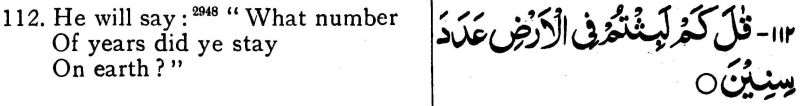

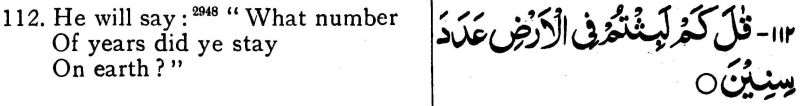

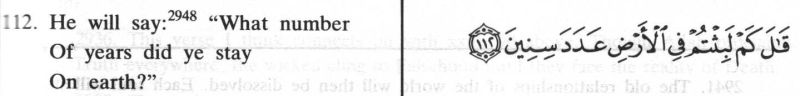

S. 23:112 |

|

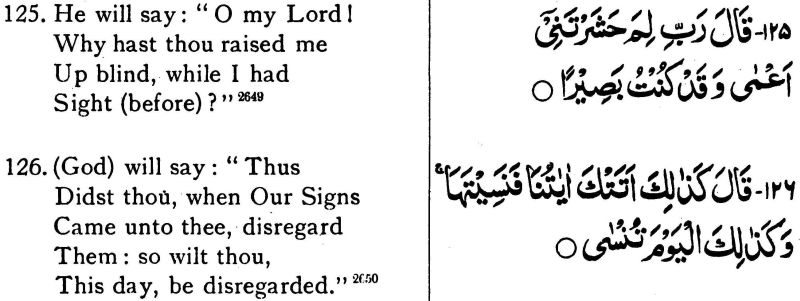

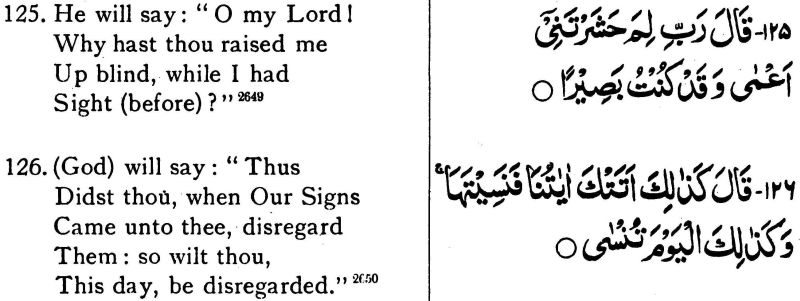

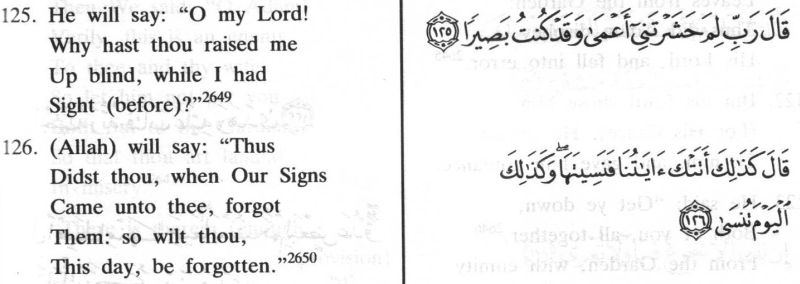

S. 20:125-126 |

|

Despite the common claim that the Qur'an is the same everywhere in the world, all manuscripts and copies of the Qur'an allegedly being identical letter for letter, better educated Muslims have long acknowledged that the Arabic text of the Qur'an exists in seven or ten or even fourteen variant readings (qira'at)[0]. For a readable introduction to this topic, see Samuel Green's paper, The Different Arabic Versions of the Qur'an.

In this article I want to point out that there are apparently not only those seven or ten or fourteen classical readings of the Arabic text,[1] but prominent Muslims are making up new readings even in our time.

My observation is based on one of the most famous versions of the Qur'an distributed in the English speaking world, the translation and commentary of the Qur'an by the late Abdullah Yusuf Ali.

In the 1946 edition of Yusuf Ali's translation, published in Pakistan, we find the following text for Sura 23:112:

He will say:2948 "What number of years did ye stay on earth?"

And the accompanying footnote states:

2948. The usual Indian reading is "Qala", "He will say". This follows the Kufa Qiraat. The Basra Qiraat reads "Qul", "Say" (in the imperative). The point is only one of grammatical construction. See n. 2666 to xxi. 4.

For Sura 21:4 we read this:

Say:2666 "My Lord knoweth (every) word (spoken) in the heavens and on earth : He is the One that heareth and knoweth (all things)."

And the accompanying footnote states:

2666. Notice that in the usual Arabic texts printed in India the word qala is here and in xxi. 112 below, as well as in xxiii. 112, spelt differently from the usual spelling of the word in other places (e.g. in xx. 125-126). Qul is the reading of the Basra Qiraat, meaning, "Say thou" in the imperative. If we construe "he says", the pronoun refers to "this (one)" in the preceding verse, viz.: the Prophet. But more than one Commentator understands the meaning in the imperative, and I agree with them. The point is merely one of verbal construction. The meaning is the same in either case. See n. 2948 to xxiii. 112.

To summarize the facts, in both places, Sura 21:4 and Sura 23:112, the verses begin with Qala (He said / He will say[2]) according to the Indian reading (the usual Arabic texts printed in India) which Yusuf Ali identifies as the Kufa qira'at. The same verses both begin with Qul (Say) according to the Basra qira'at.

Taking the two verses and footnotes together, the noteworthy fact is that Abdullah Yusuf Ali follows the Kufa qira'at (more precisely: the Hafs reading) in Sura 23:112, but chooses the Basra qira'at in Sura 21:4 and 21:112.

In effect, he mixes two different qira'at and by doing so creates a new unauthorized reading as the basis for his translation.

In other words, he does not consider either of these standard qira'at to be fully authoritative. Both of them are somewhat deficient, since one reading makes more sense in one passage, and the other reading makes more sense in other passages. Although this may appear to be a minor point to many, is this not a question of principle? Do Muslims have the freedom to tamper with "small aspects of the Quranic text" and create a new personal reading or version?

Moreover, Yusuf Ali claims that whether using qul or qala "The point is only one of grammatical construction" or "The point is merely one of verbal construction. The meaning is the same in either case." Is that really true? If it does not matter, and the meaning is the same, why then is Yusuf Ali discussing this issue at all? Why does he not simply stick with the commonly used Hafs version of the Arabic text but instead bases his translation on a different reading? Isn't he doing so because he thinks that – for whatever reason – this reading is to be preferred? In my opinion, he prefers this other reading because the meaning of it fits the context better than the usual one. In other words, the meaning is not the same, or Yusuf Ali would not have gone through the trouble of choosing another reading and then having to explain why he did so. This point will be discussed further in the next section. In fact, Yusuf Ali himself admits this in his commentary note 2767, added to S. 21:112, where he explicitly says, "The better reading is 'Say' in the imperative, rather than 'He (the Prophet) said (or says)' in the indicative mood" (emphasis mine).

And Yusuf Ali is not the only one!

Being constantly bombarded with the Muslim mantra that the Qur'an has always been the same and is identical everywhere – a claim that is nearly universally believed by Muslims – the above discovery could potentially be a shock to many. In fact, it was one contributing factor for the conversion of Farooq Ibrahim, and his article comparing the textual transmission of the Bible and the Qur'an was the place where I first discovered this particular detail.

Investigating this matter further, I was amazed to find that Abdullah Yusuf Ali is not the only translator and commentator of the Qur'an who makes up his own qira'at or version of the Qur'an. While Pickthall, Shakir, Al-Hilali & Khan and Maulana Muhammad Ali stick to the Hafs reading in all three verses, rendering qala variously as "he said", "he says", or "he will say", I have found four more quira'at mixing versions among the better known Muslim translations that have been on the market for some time, namely those done by Muhammad Asad, Rashad Khalifa, Muhammad Sarwar, and T. B. Irving.

In The Message of the Qur'an: Translated and Explained by Muhammad Asad, the author makes exactly the same choices in these three verses that we have already seen in Abdullah Yusuf Ali's translation.

Remember, the commonly used Hafs reading has qala (he said) in all three verses, Sura 21:4, 21:112, and 23:112.

Sura 21:4 according to Muhammad Asad:

Say:5 “My Sustainer knows whatever is spoken in heaven and on earth; and He alone is all-hearing, all-knowing.”

In the footnote Asad states:

5 According to the earliest scholars of Medina and Basrah, as well as some of the scholars of Kufah, this word is spelt qul, as an imperative (“Say”), whereas some of the Meccan scholars and the majority of those of Kufah read it as qala (“He [i.e., the Prophet] said”). In the earliest copies of the Qur'an the spelling was apparently confined, in this instance, to the consonants q-l: hence the possibility of reading it either as qul or as qala. However, as Tabari points out, both these readings have the same meaning and are, therefore, equally valid, “for, when God bade Muhammad to say this, he [undoubtedly] said it .... Hence, in whichever way this word is read, the reader is correct (musib as-sawab) in his reading.” Among the classical commentators, Baghawi and Baydawi explicitly use the spelling qul, while Zamakhshari’s short remark that “it has also been read as qala” seems to indicate his own preference for the imperative qul.

I disagree with Asad and Tabari. As indicated above, the meaning is not the same. Just like Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Muhammad Asad would not have taken the effort to translate a different Arabic text than the one that is printed alongside his English translation in his edition of the Qur'an – which reads qala – and then provide an elaborate footnote to explain his approach, if he could just as well have translated the usual text.

There are several dozens, if not more than a hundred, verses in the Qur'an where Muhammad is addressed by the word qul (say!). Would Muslims have any objection to simply change all instances of qul to qala “for, when God bade Muhammad to say this, he [undoubtedly] said it ..."? I doubt that even Asad or Tabari would agree with such a tampering of the text. Their justification for having two readings in this verse is ad hoc and not satisfactory. A command is not the same as a report. A description is not the same as a prescription.

Although Muslims may say, that if Muhammad was bidden by Allah to say it, he would have done so, the other way around is clearly not true. If Muhammad said something, then this must not necessarily have been by the command of Allah. Otherwise, all the hadith, everything Muhammad ever said, would be declared divine revelation. Particularly troublesome for this claim are the Satanic verses (see these articles for detailed discussions of this matter), i.e. verses which Muhammad spoke, and which Allah had to remove again from the revelation and replace them by others (cf. Sura 22:52). Also the huge scientific errors found in statements by Muhammad which are reported in the hadith (*) should not recommend this argument to Muslims.

Sura 21:112 according to Muhammad Asad:

Say:106 “O my Sustainer! Judge Thou in truth!” – and [say]: “Our Sustainer is the Most Gracious, the One whose aid is ever to be sought against all your [attempts at] defining [Him]!”

In the footnote, Asad simply states:

106 See note 5 on verse 4 of this surah.

Again, the printed Arabic text has qala but Asad translates as if it is qul.

Finally, Sura 23:112 according to Asad:

[And] He will ask [the doomed]: “What number of years have you spent on earth?”

There is no footnote to this verse. After all, Asad does not deviate here and simply translates the common Hafs reading.[2]

The next translator of the Qur'an, Rashad Khalifa, produces yet another, different mix of readings. In his translation, Quran: The Final Testament, he renders these three verses in this way:

He said, "My Lord knows every thought in the heaven and the earth. He is the Hearer, the Omniscient." (21:4)

Say, "My Lord, Your judgment is the absolute justice. Our Lord is the Most Gracious; only His help is sought in the face of your claims." (21:112)

He said, "How long have you lasted on earth? How many years?" (23:112)

Again, all three verses have qala (he said) in the usual Arabic text, but Khalifa decides to deviate in 21:112 (yet not in 21:4 as did Yusuf Ali and Asad) and translates instead the variant qul. In distinction to Yusuf Ali and Asad, Khalifa does not give any justification for his decision. Although Khalifa's translation has many footnotes, there is no explanatory note given for this verse.

For the above three Qur'an versions by Yusuf Ali, Muhammad Asad and Rashad Khalifa, I have printed editions on my shelves. On the web, I found these two translators who produced yet another reading for their versions:

| Muhammad Sarwar | T. B. Irving | |

|---|---|---|

| S. 21:4 | The Lord said, "Tell them (Muhammad), ‘My Lord knows all that is said in the heavens and the earth. He is All-hearing and All-knowing’". | SAY: "My Lord knows whatever is spoken in Heaven and Earth; He is Alert, Aware." |

| S. 21:112 | He also said, "Lord, judge (us) with Truth. Our Lord is the Beneficent One whose help I ask against the blasphemies you say about Him". | He said: "My Lord, judge with Truth," and "Our Lord is the Mercygiving Whose help is sought against what you describe." |

| God will ask them, "How many years did you live in your graves?". | He will say [further]: "How many years did you stay on earth?" |

I do not know whether Sarwar or Irving give any reasoning for their decision to assume qul instead of qala in S. 21:4 and translating it as an imperative. The web versions of their translations do not provide any notes or commentary.

M. Sarwar's translation of S. 21:4 exhibits an additional peculiarity. He translates qala twice, indicative and imperative (‘The Lord said, "Tell them (Muhammad), ..."’, i.e. ‘He said: "Say: ..."’). However, "The Lord said" is most likely just an explanatory addition to indicate that it is Allah who gives the command that follows, but "Tell them (Muhammad)" is the translation of the first Arabic word of the verse. In other words, Sarwar chose the qul-variant. Thus, Sarwar and Irving made up the same new Arabic reading as basis for their translations.

Moreover, a friend showed me an interlinear Arabic-Farsi translation of the Quran that was printed in Iran. In it, we found the same approach as we have seen in the English translations above. The Arabic text has qala in all three verses, but the translation into Farsi renders it as:

21:4 You, Prophet, say: ...

21:112 The Prophet said: ...

23:112 God will say: ...

i.e. the Iranian translator is rendering the meaning of S. 21:4 as if the Arabic had the word qul instead of qala. Thus, this Iranian translation is similar to what we have found in the versions by Sarwar and Irving.

Qira'at hopping

Taking all the above presented observations together, the result is in the following table of readings, both classical readings and those new personal "pick and choose" readings that are assumed or created as basis for various English translations:

| Hafs | Basra | Yusuf Ali / Asad | Khalifa | Sarwar / Irving / Iran | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. 21:4 | qala | qul | qul | qala | qul |

| S. 21:112 | qala | qul | qul | qul | qala |

| qala | qul | qala | qala | qala |

To summarize: Five Muslim translators of the Arabic Qur'an into the English language – Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Muhammad Asad, Rashad Khalifa, Muhammad Sarwar, and T. B. Irving – have produced three additional, new qira'at as the basis for their English translations by mixing two of the classical readings in different ways.

Perhaps one could call this approach "qira'at hopping" which I define as the following procedure: while progressing from verse to verse in the translation process, each time the translator chooses anew which reading he is going to follow for this verse.

[ Side remark: The observation that Yusuf Ali, Asad, Sarwar and Irving translate qala in S. 23:112 in the future tense, but Khalifa in the past tense is an issue that I will not pursue further in this article.[2] Most other English translations stick to the reading of qala in all three verses, and render it as "he said", "he says", or "he will say" but do not switch to qul (say!). Still, I would not be surprised, if we were to find more or other translations which do something similar to the above in other passages of the Qur'an. ]

Coming back to the question that I asked at the end of the first section, and based on the data collected in this article, the answer can only be: Yes, apparently Muslims have the freedom to tamper with "small aspects" of the Quranic text, and they are regularly creating new personal readings and versions of the Qur'an! Actually, there is even more evidence for this conclusion. However, in the interest of readability I decided not to overload the main body of this paper with endlessly many examples. Several additional instances of modern "qira'at hopping" editions are listed in Appendix 1.

Even more: Yusuf Ali's translation and commentary are officially approved!

In 1994, I was given a Qur'an as a present from a Muslim friend. This Qur'an was published in Saudi Arabia in 1411 AH (1990/1991 AD). My friend told me that he got it from the Saudi embassy in the USA, and it bears a stamp saying "Islamic Foreigners Guidance". Essentially, this Qur'an is a carefully reviewed and revised edition of Yusuf Ali's earlier work. In the preface we read:

In order to produce a reliable translation free from personal bias, ... there were two options open for consideration: the first was to select the best translation available and then adopt it as a base for further work as well as a source of reference, with the objective of revising its contents and correcting any faults in view of the objections raised against it; the second was to prepare a fresh and independent translation, starting from scratch. ...

The first option was therefore considered to be more practical, ... The translation by the late Ustadh ABDULLAH YUSUF ALI was consequently chosen for its distinguishing characteristics, such as a highly elegant style, a choice of words close to the meaning of the original text, accompanied by scholarly notes and commentaries.

The committee began revising and correcting the translation ... The committee was fully aware of all the criticisms that had been directed against this translation and which had been carefully brought to the notice of the presidency by a number of academic bodies and other involved parties. In the second stage, the entire work of this committee was referred to a number of individuals and organisations who then augmented any deficiencies in the work of the committee.

A third committee was set up to collate all their suggestions. It then compared all such views regarding specific issues, selected the appropriate one(s) and arrived at a text as authentic and defect-free as was humanly possible.

Finally, a fourth committee was formed to look into the findings of the second and third committees and to implement the recommendations made by them. Furthermore, this committee had to finalise the text by adopting the most accurate expression where needed, besides checking the notes vigilantly so as to clear any misconceptions ... (The Holy Qur-an, English translation of the meanings and commentary, Revised & Edited By The Presidency of Islamic Researches, IFTA, Call and Guidance, King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex; pp. vi-vii; bold emphasis mine)

Abdullah Yusuf Ali was an individual Muslim scholar. For the first several editions, his translation and his footnotes could be considered his personal view and decisions. For the Saudi edition that is different. Through the effort of a total of four successive committees, the translation of Yusuf Ali has been reviewed, checked and re-checked, revised and corrected by many other Muslim scholars, individuals and organisations.

Question: What was the result of their review and revision in regard to these three verses? Did they make any corrections in the 1990 Saudi edition when compared to the Pakistani edition of 1946?

Answer: They did not make any changes to the translation of these three verses, but they slightly updated the formulation in the footnotes. In the following table, I underlined the formulations that were changed:

| 1946 Pakistani edition | 1990 Saudi edition |

|---|---|

| 2666. Notice that in the usual Arabic texts printed in India the word qala is here and in xxi. 112 below, as well as in xxiii. 112, spelt differently from the usual spelling of the word in other places (e.g. in xx. 125-126). Qul is the reading of the Basra Qiraat, meaning, "Say thou" in the imperative. If we construe "he says", the pronoun refers to "this (one)" in the preceding verse, viz. : the Prophet. But more than one Commentator understands the meaning in the imperative, and I agree with them. The point is merely one of verbal construction. The meaning is the same in either case. See n. 2948 to xxiii. 112. | 2666. Notice that in the usual Arabic texts (that is, according to the Qiraat of Hafs) the word qala is here and in xxi. 112 below, as well as in xxiii. 112, spelt differently from the usual spelling of the word in other places (e.g. in xx. 125-126). Qul is the reading of the Basra Qiraat, meaning, "Say thou" in the imperative. If we construe "he says", the pronoun refers to "this (one)" in the preceding verse, viz.: the Prophet. But more than one Commentator understands the meaning in the imperative, and I agree with them. The point is merely one of verbal construction. The meaning is the same in either case. See n. 2948 to xxiii. 112. |

| 2767. See above, n. 2666 to xxi. 4. The better reading is "Say" in the imperative, rather than "He (the Prophet) said (or says)" in the indicative mood. Note that, on that construction, there are three distinct things which the Prophet is asked to say: viz.: (1) the statement in verses 109-111, addressed to those who turn away from the Message; (2) the prayer addressed to God in the first part of verse 112; and (3) the advice given indirectly to the Believers, in the second part of verse 112. I have marked these divisions by means of inverted commas. | 2767. See above, n. 2666 to xxi. 4. The better reading is "Say" in the imperative, rather than "He (the Prophet) said (or says)" in the indicative mood. Note that, on that construction, there are three distinct things which the Prophet is asked to say: viz.: (1) the statement in verses 109-11, addressed to those who turn away from the Message; (2) the prayer addressed to Allah in the first part of verse 112; and (3) the advice given indirectly to the Believers, in the second part of verse 112. I have marked these divisions by means of inverted commas. |

| 2948. The usual Indian reading is "Qala", "He will say". This follows the Kufa Qiraat. The Basra Qiraat reads "Qul", "Say" (in the imperative). The point is only one of grammatical construction. See n. 2666 to xxi. 4. | 2948. The Hafs reading is "Qala", "He will say". This follows the Kufa Qiraat. The Basra Qiraat reads "Qul", "Say" (in the imperative). The point is only one of grammatical construction. See n. 2666 to xxi. 4. |

The fact that the Saudi edition has slightly updated footnotes proves that these scholars did not accidentally overlook these verses and accompanying footnotes. Verses and commentary were checked and then only minimally revised by replacing, for example, the expression "the usual Indian reading" by "the Hafs reading". The explanation and reasoning remained substantially the same. Therefore, I conclude that both the translation and the footnotes by Yusuf Ali were officially approved by this authoritative body of Muslim scholars.

In other words, the Saudi Muslim institution or authoritative Islamic body, called The Presidency of Islamic Researches, IFTA, Call and Guidance, has approved of creating new readings by mixing some of the classical qira'at. They have endorsed "qira'at hopping" – at least for translations of the Qur'an into foreign languages.

Understanding Yusuf Ali's note 2666

In order to fully understand Yusuf Ali's argument for his choice of a different reading, we need to look at the Arabic text. The following are scanned images of the 1946 edition of Yusuf Ali's Qur'an, printed in Pakistan.

S. 21:4 |

|

S. 21:112 |

|

S. 23:112 |

|

S. 20:125-126 |

|

Again, Yusuf Ali's first statement in his note 2666 on 21:4 was:

Notice that in the usual Arabic texts printed in India the word qala is here and in xxi. 112 below, as well as in xxiii. 112, spelt differently from the usual spelling of the word in other places (e.g. in xx. 125-126).

Indeed, in the Arabic text of the 1946 edition, the word qala is written

in S. 21:4, 21:112 and 23:112 as  , but it is

, but it is

in S. 20:125 and most other places.

in S. 20:125 and most other places.

What is the difference? In these three verses, the "consonantal text" (rasm) of the first word consists of the two letters qaf-lam, and only the diacritical marks placed above the letters tell the reader that the word should be pronounced as qala instead of qul. On the other hand, in S. 20:125, 126 and other places, the rasm text consists of the three letters qaf-alif-lam which allows only the pronunciation qala, but not qul.

This is also in agreement with the comment on S. 21:4 by Muhammad Asad:

... In the earliest copies of the Qur'an the spelling was apparently confined, in this instance, to the consonants q-l: hence the possibility of reading it either as qul or as qala. ...

Tampering with the Arabic text?

Amazingly, the Saudi revision committees approved the translation and the commentary of Abdullah Yusuf Ali – as we saw above – and then they changed the Arabic text!

Comparing the Arabic text in the 1946 Pakistani edition and the 1990 Saudi edition, we find that the first word in S. 21:4 was changed in the later Saudi edition[3], and is now written differently than before. Here is a comparison table, displaying the first word of each of these verses in the two editions:

| 20:125 | 21:4 | 21:112 | 23:112 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 edition |  |

|

|

|

| 1990 edition |  |

|

|

|

The Saudi publishers changed the Arabic text. They added the letter alif in S. 21:4 so that the rasm of qala is now the same in 20:125 and in S. 21:4, i.e. qaf alif lam.

[ Some explanations for those not familiar with Arabic: The rasm of a word are the letters that are left when all vowel signs, diacritical marks (dots) and other markers for the correct pronunciation are removed. This is important since the earliest manuscripts of the Qur'an were rasm texts. The markers are later additions. Although, visually, the first words of Sura 21:112 and 23:112 appear to be different in these two editions as well, they are not. The stroke between the qaf and the lam is a little alif, added to the rasm proper to indicate a long a-sound, as if the rasm contained an alif. It doesn't matter whether this little alif (stroke, "dagger alif") is written above the qaf, as in the 1946 edition, or above the line between the qaf and the lam, as in the 1990 edition. In both cases, they are merely markers for the correct pronunciation and the rasm has not changed. In S. 21:4, however, a full alif was inserted, and thus the rasm of the word changed. ]

I will leave it to the readers to decide for themselves whether making such changes to the Arabic text of the Qur'an is acceptable or not, and whether or not they consider this to be a corruption of the Qur'an.

But one thing is clear, their change to the Arabic text renders their newly revised and approved commentary unintelligable. Again, their note on S. 21:4 states:

2666. Notice that in the usual Arabic texts (that is, according to the Qiraat of Hafs) the word qala is here and in xxi. 112 below, as well as in xxiii. 112, spelt differently from the usual spelling of the word in other places (e.g. in xx. 125-126). ...

How can the reader notice this when it is not true for the Arabic text that is printed together with this commentary? Moreover, if that is indeed so in the usual Arabic texts, i.e. in the reading of Hafs, but it is not so in the Saudi edition, what kind of unusual Arabic text have the Saudis printed in this edition? And what is their justification for doing so?

On the other hand, if changing the rasm text of the Qur'an by turning little alifs into full alifs (and vice versa) is acceptable, why did the Saudi publishers make the change in only one of the three discussed instances? Why did they change the spelling of qala only in S. 21:4, but not in S. 21:112 and 23:112? What is the reason for their inconsistency?

Further reading

A ‘Perfect’ Qur'an, or ‘so it was made to appear to them’? is a book that provides a wealth of information on changes in the Arabic text of the Qur'an. The above example is not mentioned in it. The disappearance of several thousands of alifs from the rasm text of the Qur'an is discussed in some detail in chapter XIII, section b/ ‘Dagger-Alifs’ (*). Chapter VII (*) is also particularly relevant in this context.

Theodor Nöldeke's classical work Geschichte des Qorans ("History of the Qur'an", written in German) lists many variant readings in the first chapter of Part 3 ("Dritter Teil"). This book can be accessed here.

Appendix 1: Even more Qira'at Hoppers

Apart from the "older" translations of Yusuf Ali, Sarwar, Irving, Khalifa and Muhammad Asad, which have been examined in the main part of this paper, there are several more recent English translations of the Qur'an in which the Muslim authors prove that this kind of creativity is not something of the past. Far from it! Besides repeating some of the choices we have already seen above, they also produce some new variations in their renderings of these three verses.

First, English Translation of the Meaning of Al-Quran, The Guidance for Mankind, translated by Muhammad Farooq-i-Azam Malik, The Institute of Islamic Knowledge, Houston, 1997:

Tell them: "My Lord has knowledge of every word which is spoken in the heavens and the earth, and He hears all and knows all." (21:4)

Finally the Prophet said: "O Lord! Pass Your Judgment with fairness. And O People! Our Lord is most Compassionate, Whose help we seek against the blasphemies you utter." (21:112)

They will be asked: "How many years did you live on earth?"(23:112)

Malik's translation is similar to Sarwar, Irving and the Iranian version. He chose qul for S. 21:4 and qala for S. 21:112 and 23:112.

Second, there is Shabbir Ahmed; in his The Quran as it Explains Itself, 4th edition, 2007, we find the verses translated this way:

The Prophet said, “My Lord knows every word that is spoken in the High and the Low. He is the Hearer, the Knower.” (21:4)

Say, “My Lord! Help us establish Your Rule. Our Lord is the Beneficent Whose help is sought against whatever falsehood you ever ascribed to Him.” (21:112)

He will ask, “What number of years did you spend on earth?” (23:112)

In other words, Shabbir Ahmed made a similar choice as Rashad Khalifa in assuming the first word of 21:112 as being qul instead of qala, while keeping qala for 21:4 and 23:112.

Third, The Koran: Complete Dictionary & Literal Translation, prepared by: Mohamed Ahmed & His Daughter Samira, 1994, has:

He said: "My Lord knows the saying/opinion and belief in the skies/space and the earth/Planet Earth, and He is the hearing/listening, the knowledgeable." (21:4)

Say: "My Lord, judge/rule with the correct/truth, and our Lord (is) the merciful, the seeked help/assistance from, on (about) what you describe/categorize." (21:112)

Say: "How much/many number/numerous years you remained in the earth/Planet Earth?" (23:112)

This is a new variant; these translators are keeping qala for 21:4, but assuming qul instead of qala for 21:112 and 23:112.

The next version has been published under different titles, every new edition apparently getting a new title: (1) The Message: God's Revelation to Humanity, ProgressiveMuslims.org, 2003 (paperback), (2) The Message: A Literal Translation of the Final Revealed Scripture, 2002-2005, Free-Minds (Source), (3) The Message: A Pure and Literal Translation of Al-Qur'an, (online version, updated September 20th, 2007), (4) The Message: A Pure and Literal Translation of the Qur’an, The Monotheist Group, 2008 (PDF file offered at free-minds.org). I am quoting here from version (4), which has the most recent date attached to it:

Say: “My Lord knows what is said in the heavens and in the Earth, and He is the Hearer, the Knower.” (21:4)

He said: “My Lord, judge with truth. And our Lord, the Almighty, is sought for what you describe.” (21:112)

Say: “How long have you stayed on Earth in terms of years?” (23:112)

This is yet again a new mixture of choices for qul and qala in these verses. These "Progressive Muslims" are keeping qala for 21:112, but are assuming qul instead of qala for 21:4 and 23:112. No explanation is given. In fact, they are proud of using neither parentheses nor footnotes in their edition (Preface, page i).

Finally, Quran: A Reformist Translation, Translated and Annotated by: Edip Yuksel, Layth Saleh al-Shaiban, Martha Schulte-Nafeh, Brainbow Press, 2007, sources (1, 2), renders these three verses as:

Say, "My Lord knows what is said in the heavens and in the earth, and He is the Hearer, the Knower." (21:4)

Say, "My Lord, judge with truth. Our Lord, the Gracious, is sought for what you describe." (21:112)

Say, "How long have you stayed on earth in terms of years?" (23:112)

At first glance, this may look like Edip Yuksel and his team have chosen the Basra qira'at as the basis for their translation, but that is not the case. There is no mentioning of them following any of the established qira'at for their translation. Moreover, there are no explanatory notes on S. 21:4 and 23:112, but there is a footnote attached to S. 21:112 which reveals that they have entirely different reasons for their choices:

021:112 The mathematical system of the Quran leads us to read the word QWL not as a past tense verb, but as a declarative one. Our choice is supported by the original spelling of the word, which has no letter "A" after the first letter, and thus, supports our reading. Furthermore, when read starting from verse 108, our choice fits best to the flow of the language. This is also supported by the numerical semantics (nusemantics) of the Quran: the frequency of the word QaLu (they said), as used for God's creation is equal to the frequency of the divine command QuL (say), both being 332 times. In other words, for each "they say," God tells us to "say" something. These two words are not necessarily used in successive pairs. (underline emphasis mine)

Edip Yuksel is one of the main proponents of the alleged mathematical miracle of the Qur'an, and he needs to assume qul in these three places so that his numbers come out right. Note that he did not only adjust one word of the Hafs text, but he had to change (at least?) three instances of qala to qul in order to increase the count of qul to the desired number. In other words, the correct text of the Qur'an is determined based upon human counting theories. If the text – as it is – does not yield the right numbers, it is adjusted/corrected by subjecting it to certain numerical theories.

Including the above data from those newer translations into our table of "qira'at hoppers", it now becomes:

| Hafs | Basra | Yusuf Ali / Asad | Khalifa / Sh. Ahmed | Sarwar / Irving / Malik | M. & S. Ahmed | Progressive | Reformist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. 21:4 | qala | qul | qul | qala | qul | qala | qul | qul |

| S. 21:112 | qala | qul | qul | qul | qala | qul | qala | qul |

| qala | qul | qala | qala | qala | qul | qul | qul |

One can hardly avoid the conclusion: Anything goes!

Note: Although the columns of Basra and Reformist are equal in these three words, I have created two separate columns for them since the authors of the Reformist Translation have not chosen these variants in these verses because they follow the Basra qira'at (they most likely deviate from Basra in most other verses in which there are differences), but because they wanted to satisfy certain counting theories regarding how often particular words are supposed to appear in the Qur'an.

There exist many more English translations of the Qur'an (*) which I am currently not able to examine, because they neither exist online, nor do I have access to a printed copy. I expect that some of those other translations will stick to the Hafs reading, like Pickthall and Al-Hilali & Khan, and some of them will again deviate from it like those listed above.

Appendix 2: Other Arabic-English Qur'an Editions

Most other English editions of the Qur'an that I have seen translate the first word of these three verses (qala) as "he said" in S. 21:4 and 21:112, and "he will say" in S. 23:112.[2] More interesting is the question which Arabic text is printed in these editions.

The following table only looks at the spelling of qala in S. 21:4, 112, 23:112. There may be many other differences between in these Arabic texts when compared among each other. Based on the discussion in this paper — and in want of a better name — I will call the two text types the 1946-Pakistani text type and the 1990-Saudi text type, and classify other editions according to this convention.

| 21:4 | 21:112 | 23:112 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946-Pakistani text type |  |

|

|

| 1990-Saudi text type |  |

|

|

(Some) Versions that use the 1946-Pakistani text type:

(Some) Versions that use the 1990-Saudi text type:

Looking only the the Pakistani and Saudi editions of Yusuf Ali's version of the Qur'an, one might have come to the conclusion that there was perhaps a time when Muslim publishers changed from one text to the other. This is apparently not true. Both types of Arabic texts of the Qur'an are currently used. Both are still in print today.

Endnotes

0. A more exact transliteration of the word would be qirâ’at (singular) and qirâ’ât (plural) with â indicating a long a-sound. Also the word qala, meaning "he said", which will be referred to many times in this article, would more properly have to be transliterated as qâla. However, for simplicity's sake, I will only use the spellings qira'at and qala throughout the text.

1. Even more variants of the Arabic text than those classical readings are collected in ‘Abd al-‘Âl Sâlim Makram (wa) Ahmad Mukhtâr ‘Umar (i‘dâd), Mu‘jam al-qirâ’ât al-qurânîyah, ma‘a muqaddimah fî qirâ’ât wa ašhar al-qurrâ’, vols. I-VIII, al-Kuwayt: dhât as-salâsil, 1st edition 1402–1405/1982–1985. Apart from those seven or ten or fourteen authorized variant readings, there are many unauthorized variants of the text discussed by early Muslim scholars. Moreover, additional textual variants are found in old Koran manuscripts.

2. Qala is grammatically in the past tense and means "He said". However, since the context of S. 23:112 is the Last Judgment, a future event, Yusuf Ali, as well as most other translators, decided that rendering the verb in the future tense instead of the past tense is more appropriate (some even changing the active to the passive voice). This observation is the topic of another article.

3. The following are scanned images from the 1990 revised edition of Yusuf Ali's Qur'an, printed in Saudi Arabia.

S. 20:125-126 |

|

S. 21:4 |

|

S. 21:112 |

|

S. 23:112 |

|

The Text of the Qur'an

Answering Islam Home Page